VIS issue 3, History Now, presents expositions where artistic practices develop and explore historical manifestations in the now. The eight contributions attempt in different ways to recreate and reread the past. In doing so they create possibilities for reconsidering history rather than repeating it.

VIS #3 - THEME: HISTORY NOW

Roland Barthes writes in the introduction to Camera Lucida how he happened on a photograph taken in 1852 of Napoleon’s youngest brother Jerome. In a moment of amazement he realises that “I am looking at the eyes that looked at the Emperor”. This almost necromantic feeling may occur in the meeting with photographs – in the experience of history coming alive for a moment. A lived history is otherwise found in actions, gestures, and behaviours – in different distinct or discreet practices – passed down from person to person, from one generation to the next. Art too – that is, visual arts, music, literature, film and dance – is also a site in which a historical spirit can be teased out into the present. The same goes for politics – to apply a hold on history and violently force selected, often false, memories on contemporary society, is a speciality of the authoritarian regime. And in order to complete this operation art is frequently used: heroic monuments, poems, songs, paintings… Indeed the French film essayist Chris Marker argued that the only politically meaningful history is the one that is revealed in our time. Marker was obsessed with Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo. He had seen it 19 times and left no stone unturned in trying to retrace all the film’s locations. According to Marker “only one film had been capable of portraying impossible memory, insane memory” – Vertigo.[1] He called travelling in the footsteps of this film and text a pilgrimage. In Marker’s case it is an action that uses the real present in the fiction as a starting point and places it in history. The film's locations – the florist Podesta Baldocchi, the Museum of the Legion of Honor, the cemetery at Mission Dolores where the main character Madeleine came to pray at the grave of a woman – all these real places from the fiction are ‘re-performed’ by Marker in his own film Sans Soleil.

For the third issue of the journal VIS – History Now – we were particularly looking for expositions where artistic practices developed and explored historical manifestations in the now. And the eight contributions that were chosen attempt in different ways to recreate and reread the past.

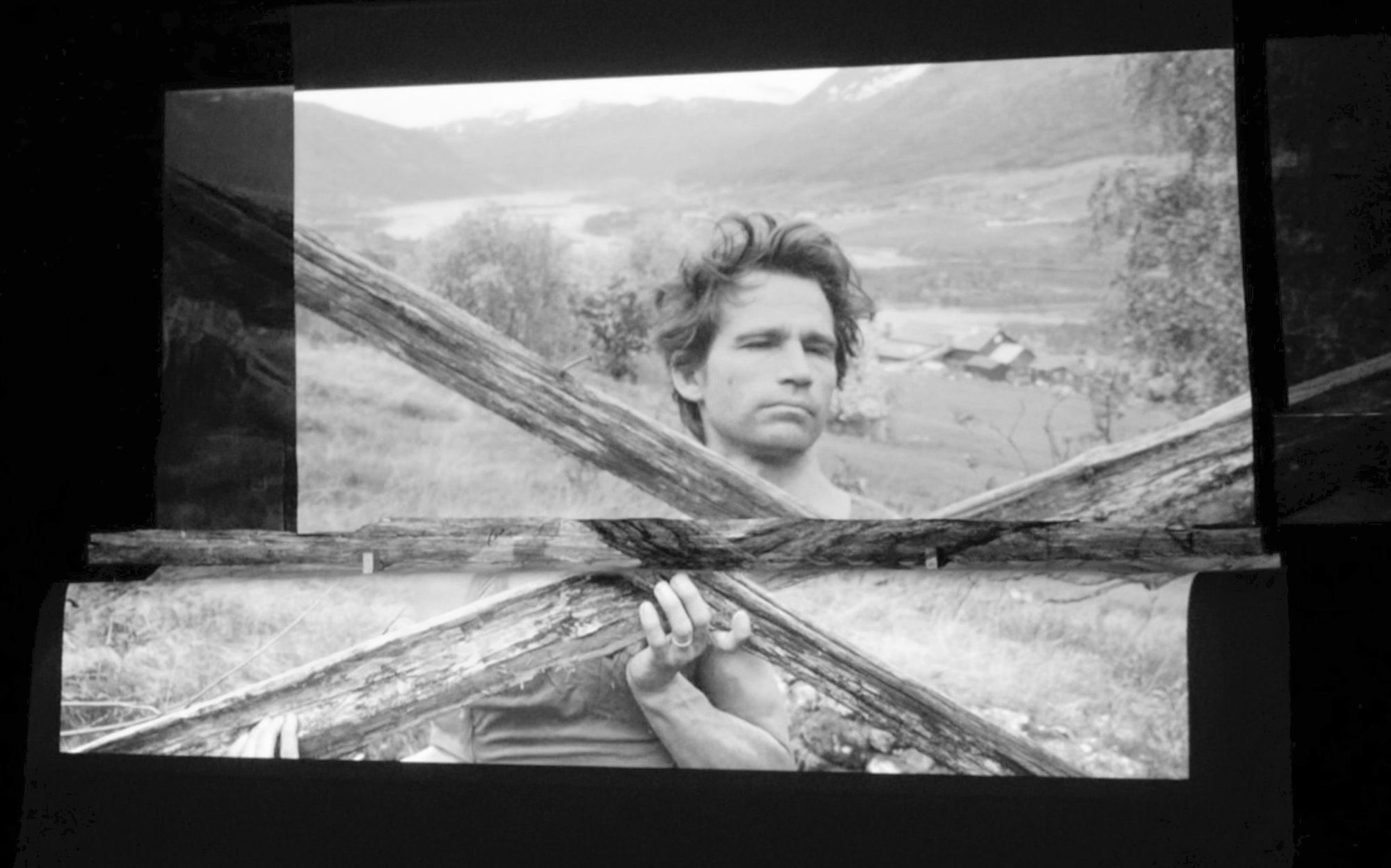

Marianna Christofides, whose essay film Days in Between in many ways references Chris Marker’s work, explores themes of loss, omission and disorder in relation to the violent history of the Balkans. The image of the river plays a crucial role in Days in Between, both as a geographical border and a site which evades a rational, cognitive mapping of a place; the continual transformation of the river and its elusive quality constantly demands new, temporary ‘re-readings’.

The dancer Otto Ramstad performs his own unique take on ‘artistic family history’ as a method with which to investigate the history of his Norwegian ancestors. Ramstad’s corporeal techniques, in combination with written reflections and speculations, establish a bond to the country that his family once inhabited and that he himself knew very little about. There is a desire here to imagine oneself into a body living in the Norwegian countryside 100 years ago and then to ask how this has affected the way we live in our bodies today.

Mareike Dobewall also employs the body in order to establish a relationship to a historical site, ‘a sonic dialogue’ as she calls it. During a two-week workshop Dobewall and the non-professional choir ‘Peenechor’ explored two neglected buildings in the former East German city of Demmin. As vocal experiments took place around the buildings the participants’ memories were stirred and stories other than those officially told were able to emerge. The exercise turns the German word for history – Geschichte – into the plural Geschichten, now meaning stories.

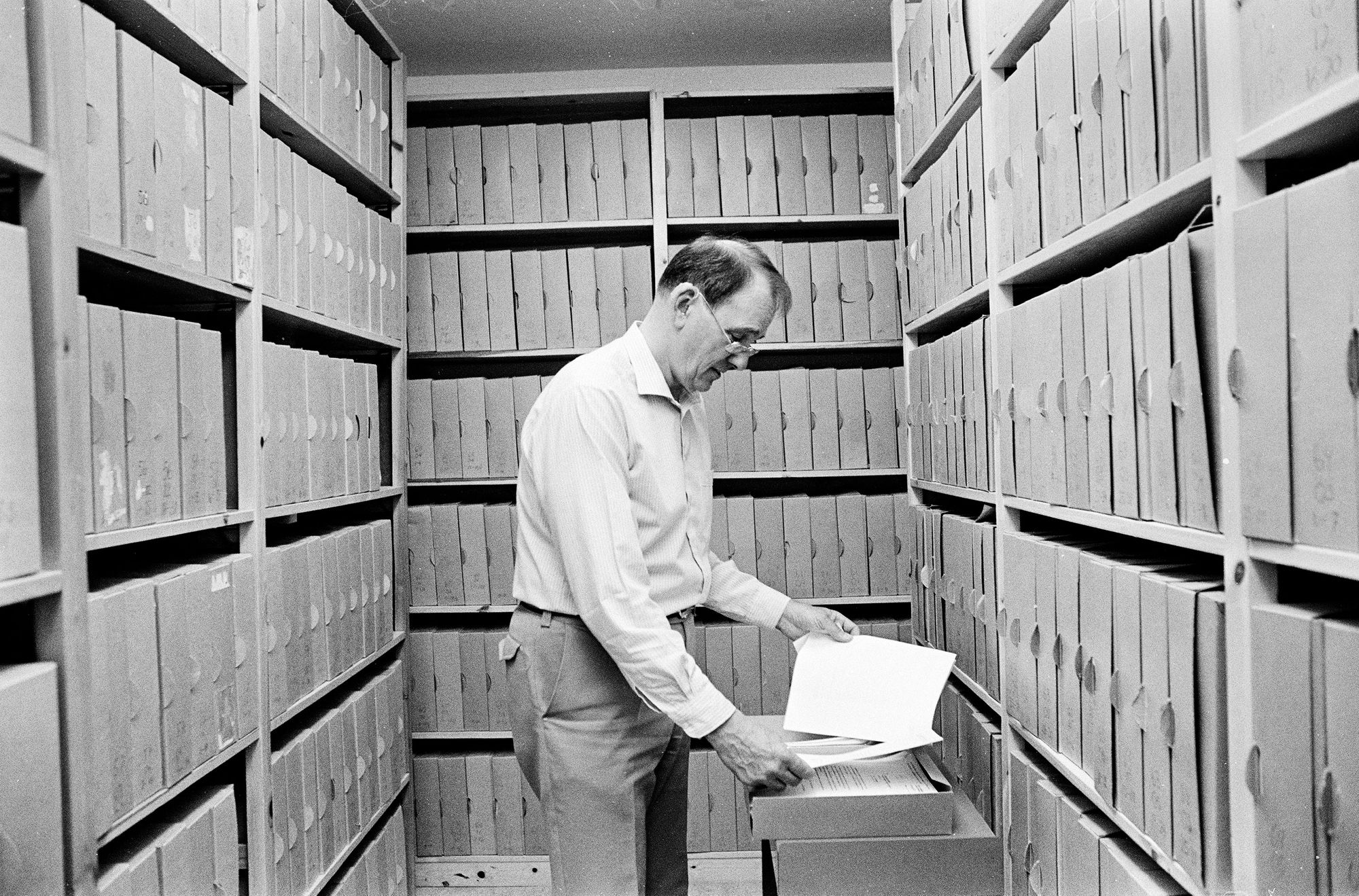

In the case of Tina Carlsson it is her own body that carries the memories. Using her notion of the ‘folkhem-marinated body’ as a starting point the artist tries to sketch the “nodes from which the folkhem unfolded and how that created the preconditions for certain people to feel at home while others were excluded”. An important part is played by Carlsson’s dialogue with her father, who in many ways was right in the midst of the social democratic movement and the administration of the folkhem.

Artists Björn Larsson and Carl Johan Erikson both chose non-combatant service when they did their military service in Sweden during the 1980s.They went through the same interviews, which they have now recreated in the film Serious Personal Conviction. In the film’s parallel frames we encounter on the one hand middle-aged men looking back on their decision to refuse to carry weapons and on the other young people today who are faced with the same kind of issues regarding the right to take someone else’s life. And so material from a not too distant past is employed to ask questions about the present moment.

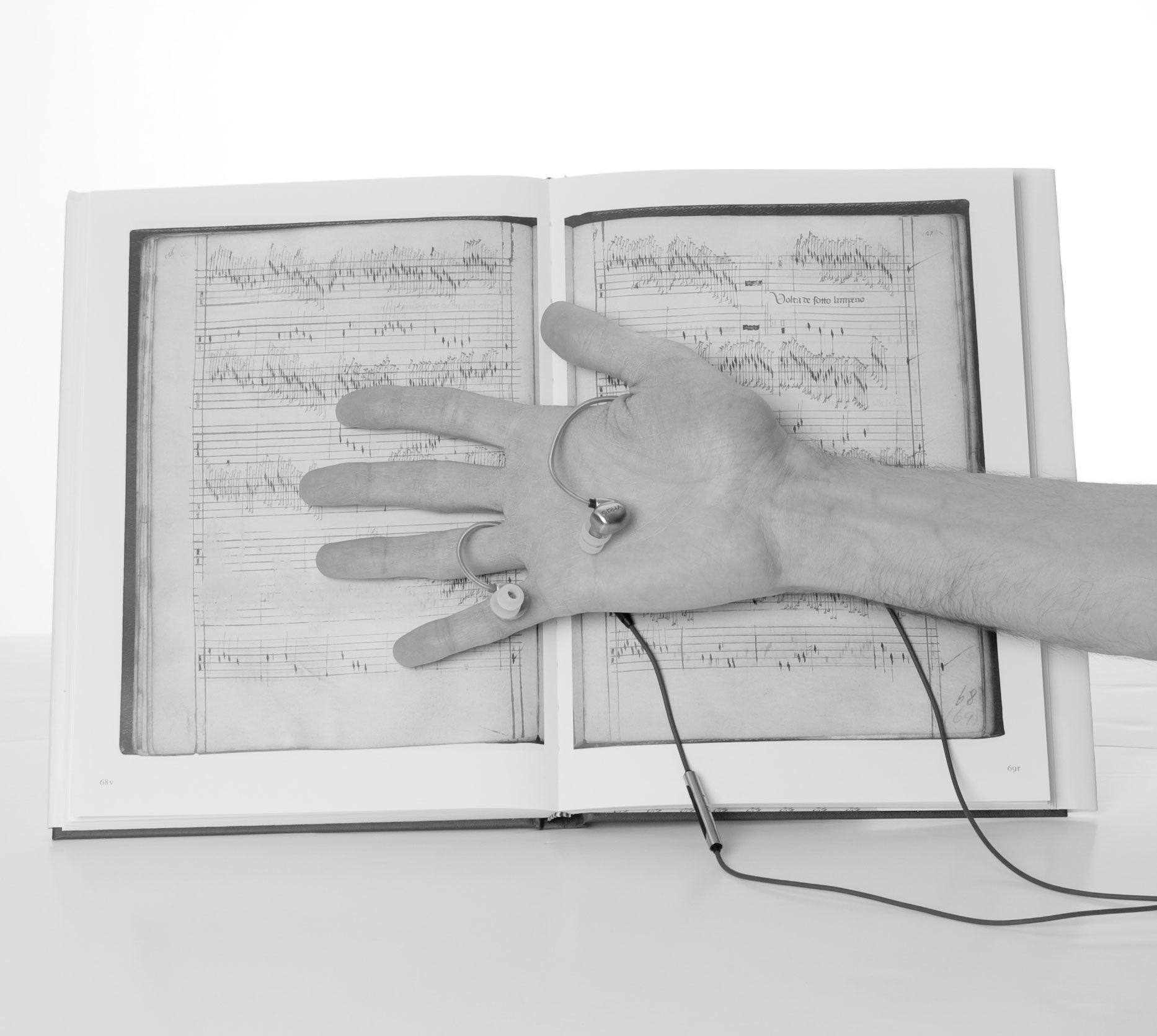

Jostein Gundersen, Ruben Sverre Gjertsen and Alwynne Pritchard take on historical material very directly: that is late Middle Age- and early Renaissance music, particularly polyphonic music from Italy made around the year 1400. Within the field of Historically Informed Performance (HIP) complex relationships between composition and improvisation are introduced. Through the exposition’s blend of text, sound, video, and scores we follow a process that when it succeeds becomes “a combination of virtuosity, curiosity, openness, trust, and willingness to experiment”.

Musician and writer Eivind Buene, on the other hand, historicises pieces by Franz Schubert with a masterly methodology. By transforming these pieces into lounge music he creates a refraction between two time strata. In the project he strives to generate a multifaceted experience through what he calls ‘telescopic listening’. It is a way of listening to music where the telescopic brings history closer and where different, yet similar, eras coexist in the now.

Finally Behzad Khosravi Noori’s contribution The Life of an Itinerant Through a Pinhole is built on archive material his maternal grandfather left behind. Between 1956 and 1968 Khosravi Noori’s grandfather, Gholamreza Amirbegi, took an enormous amount of photos around the working class neighbourhoods of Teheran, where he lived with his family. By reactivating in exhibitions and performances the particular pinhole camera his grandfather had used (a precursor to the Polaroid camera) the artist raises questions about unconscious colonial memories and stories that go far beyond the working class neighbourhoods and include the entire global south.

Below is a presentation of the open call text that these expositions are all a response to.

Magnus Bärtås, Editor, VIS #3

[1] As stated in the female voice-over narration to Marker's Sans soleil (1982).

CALL VIS ISSUE 3, HISTORY NOW

The writing of history and the interpretation of events from the past become incredibly powerful and emotive questions of identity in families, local contexts, and nations. Ways of dealing with historical events, cultural inheritance matters and cultural canon issues are constantly being negotiated, forever becoming questions of national self-image, of remembering and forgetting, of inclusion and exclusion, of elimination and (re)discovery. Our stories and interpretations of history give rise to the fundamental questions of existential politics: where do we come from, where are we, and where are we going?

For this issue, we’re looking for expositions in which artistic practice addresses manifestations of history in the present. There has long since been reciprocal exchange between artistic methods and practice and historical theory, music history, and history of science, broadening discussions about the relationships between history and literature, word and image, fiction and reality, film and historical material. Archival practices have taken a prominent role in contemporary art. Historico-performative practices such as re-enactments and other recreation and re-views of events, historical material and historical techniques have emerged in theatre, performance, dance, film and music. Here, there are possibilities to activate affect and knowledge that do not necessarily concern the battle for memory, history and culture. The philosopher Paul Ricœur calls doing a re-enactment a re-affectation of the past in the present. [1] Re-enactment is a task of re-thinking [re-penser] and not of reliving [revivre]. Someone, or something, acts as a stand-in for the past in such situations. With the stand-in, a self acts as an other, temporarily freeing the I, but also offering a fundamental opportunity for knowledge and insight. With History Now, VIS extends an invitation to re-think, to tread new paths alongside the ruts of history, and to try to understand ourselves through history.

Magnus Bärtås, editor of VIS issue number 3.

[1] Paul Ricœur, ”Den berättande tiden”, in Från text till handling, en antologi om hermeneutik, red. Peter Kemp & Bengt Kristensson, Stockholm: Brutus Östlings Bokförlag Symposion 1993, p. 223.

Credit Line Front Image:

Days In Between, 2015 (film still)

single-channel 16mm film digitally transferred, color & b/w, stereo, 40:00

© Marianna Christofides / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020